Theme

Observe the relationships between job areas to create a visual representation of the organization of labor in order to recognize microstructures such as “interfaces” within the white and blue collar subsystems.

Material

- Workplace observations

Discussion

In the prior section I introduced the two major labor subsystems in manufacturing to provide a high-level perspective of how labor is generally delineated. In this section I will dive deeper into the subsystems to better show the kinds of microstructures that arise in some organizations and to visualize labor as a network. I believe that in representing work distribution in this way it will make it easier to understand how this kind of perspective can nest itself within an optimization context i.e. an industrial engineering context. This section will only identify workers within the broader context of their domain and the next section will show how labor shifts within the organization due to the social expectations of both kinds of labor and its subsequent function allocation. It is important for me to bring up here that this earlier blog content is meant to show the initial state of labor networks prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. In this way I will be able to explain and visualize later how the initial organization of labor alongside social norms restricted the way labor could readjust during the pandemic.

It is worth noting I have failed to mention that there are some generalizations I make about who does certain kinds of tasks, but these are only drawn directly from my experiences within certain manufacturing organizations. This poses a minor issue for universality, however, I expect that discussing and mapping labor in this way can develop a language that others may use to better understand their own organizations in these contexts.

Who Works Where?

One of the most marked distinctions (in my opinion) of white collar labor in manufacturing is the contemporary mode of compensation. That is, this type of labor is typically a salaried position as opposed to the traditional hourly rate or piece-rate compensation of blue collar labor. There are certainly unique situations in which this is not the case, but overall it tends to hold true.

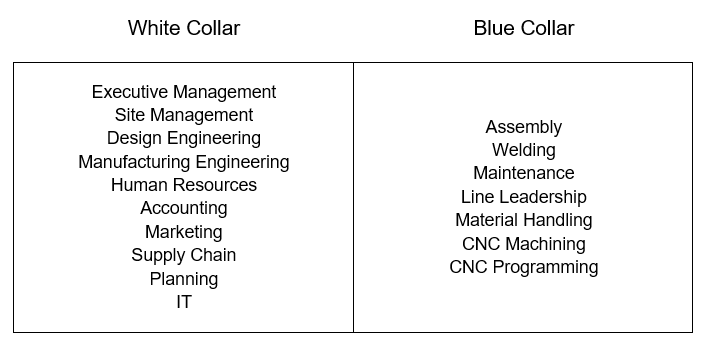

As mentioned before, the labor of white collar workers can be both physically and temporally unbounded. So it is good to remember that although I draw a defined border when modeling this labor it can occur quite literally anywhere and anytime. Before modeling this, I’ll summarize some the qualities mentioned in the prior section, but I find it will be more helpful to list the actual job areas considered white collar (see table 1).

| White Collar Qualities | White Collar Job Areas |

|---|---|

| Physically unbounded | Executive Management |

| Temporally unbounded | Site Management |

| Creatively free | Design Engineering |

| Unmonitored | Manufacturing Engineering |

| Non-repetitive | Human Resources |

| Non-standardized processes | Marketing |

| IT |

Although I don’t like to imagine the two types of labor as entirely dichotomous, for the sake of illustrating, I will pretend that they are. Generalizing our labor types in this way helps us develop our framework within the context of manufacturing in a much simpler way. That being said, a list of blue collar qualities and job areas to satisfy our current objective may look like table 2.

| Blue Collar Qualities | Blue Collar Job Areas |

|---|---|

| Physically bounded | Assembly |

| Temporally bounded | Welding |

| Creatively constrained | Maintenance |

| Highly monitored | Line Leadership |

| Highly repetitive | Material Handling |

| Standardized processes | CNC Machining |

| CNC Programming |

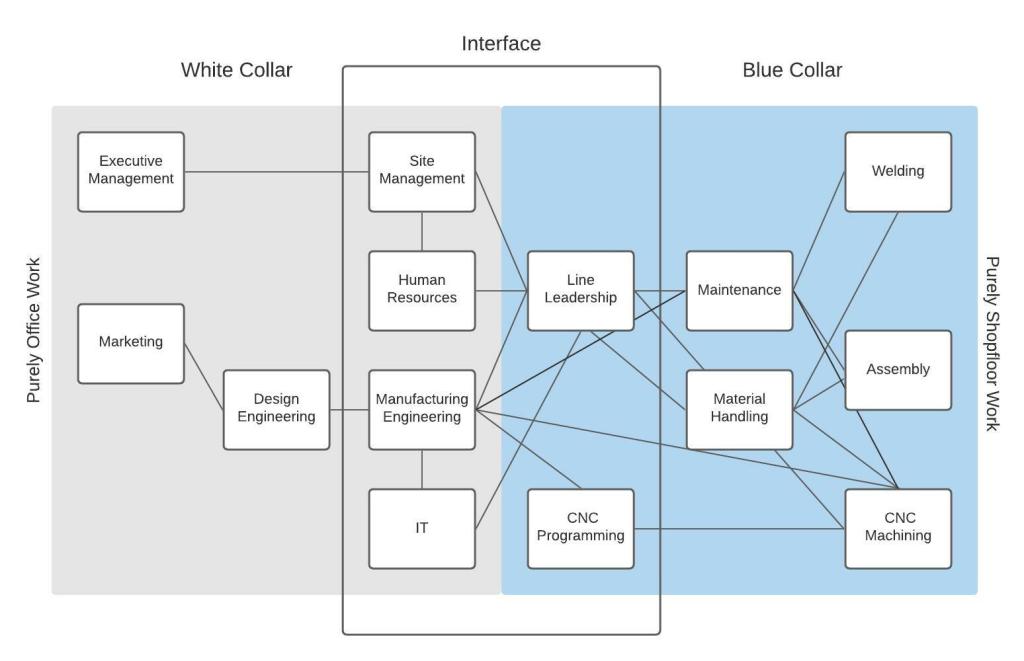

Now if we were to align these professions according to our diagram from the previous section, we notice how there isn’t an immediately obvious tertiary group (see figure 1). In fact, if we were to focus solely on on the descriptors that differentiate “office workers” from “shop floor workers” to map labor in the organization it gives us a pretty poor representation of how work may be managed. It is specifically this oversight in our day-to-day observations that I believe causes some of the most blaring organizational issues to elude us. It’s not simply a matter of who does what kind of labor or group of tasks in an organization that defines how labor is distributed, it is both the relationship between workers to each other and to a workspace that gives us the best kind of representation.

In figure 2 below, I show that if we take into consideration the most frequent interactions between workers of certain job areas and pay attention to where the majority of their work lies, we can see much more clearly how a tertiary group may arise. So although a manufacturing engineer is also a white collar worker (like the design engineer) who may work at a desk often, it is the relationship with those confined to the shop floor that also binds this engineer to the shop floor.

Summary

Industrial engineers typically focus on the worker as a person who has to do certain tasks within a certain space. Then they “engineer” as much as they can within that framework. However, as I’m trying to show, this ignores quite a lot about the nature of the work they’re designing around. That is not to say that industrial engineers only think about workers in this way. However, the majority of methodologies for analyzing work and workspaces do not take this into account and therefore cannot handle the other kinds of factors that define how work is done.

I understand that this model is extremely rudimentary and purely qualitatively developed. However, with appropriate qualitative and quantitative methods a very robust and highly detailed map of labor relationships could be developed. What we can do with this is start to show how labor may move or flow within a network with these kinds of relationships (this will be the theme of the next section). In doing so, we can start to ask more questions not just from an engineering perspective, but also a more anthropological one. This will better equip us to not only notice what it is that shapes and defines labor but also what changes can be made to distribute labor in a way that can prevent employee burnout.

Leave a comment