Theme

Recognize that manufacturing organizations are composed of two major labor subsystems; blue collar (direct, shop floor, or manual labor) and white collar (indirect, desk, or administrative labor.) These two systems manage different kinds of labor within the same organization using different methods of evaluating and managing productivity. The interaction between these two subsystems creates its own kind of labor processes.

Materials

- Melissa Gregg – Counterproductive: Time Management in the Knowledge Economy (Introduction, pp. 3-21)

- Darina Lepadatu and Thomas Janoski – Framing and Managing Lean Organizations in the New Economy (Introduction, pp. 1-28)

Discussion

What are we trying to answer, and why?

The U.S. is experiencing in 2021 what some are referring to as a “Turnover Tsunami” or “The Great Resignation.” It is currently understood that the unemployment rate is at the highest it has been in many years according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, meanwhile there are a great number of vacant jobs that need filling. This begs asking the question, why are people choosing not to work? This is forcing many companies to look at what they can do in the workplace to retain employees by increasing worker satisfaction metrics such as work-life balance or compensation. This is of great concern to these companies because they obviously have work that needs doing, but filling vacant jobs can be costly, especially in the current landscape of outsourcing hiring processes to recruiters and software.

What I have noted from various articles in regards to this employee retention problem is the ubiquitous burnout. This lead me to start wondering about how labor is distributed in these organizations, the structures that shape it, and how the organization of labor might affects the attitudes and behaviors toward work. This independent study, at its core, tries to answer the questions: how are organizations structured, how does this affect their sustainability, and how can industrial engineering try to improve organizational sustainability to withstand environmental changes such as a pandemic? In trying to answer these questions we have to interrogate what we know about these organizations not just from within the field of industrial engineering but also outside of it. This blog could then serve as a pedagogical tool for reframing the perceptions and scope of work in the field by introducing vocabulary and methodologies from the humanities and situating them within engineering orthodoxy.

Blue Collar Labor

To start interrogating these systems, it is important to note that industrial engineering specifically in its curriculum at UW-Milwaukee and as I’ve seen in the workforce focuses almost entirely on the productivity and efficiency of blue collar labor. It makes sense, especially with the understanding that the field was borne of the industrial revolution. Because of this, through Lean type methodologies, the field of blue collar labor has been highly engineered. This manifests in work being required to follow certain tasks in a specific order using specific tools within a specific space to accomplish a specific hourly rate. It is this rate that is under constant scrutiny, because any extreme deviations from norm are indicative of systemic or process problems that must be investigated. Although this is the primary focus of industrial engineering, this very manual and repetitive work is not the only kind of labor within a manufacturing organization.

White Collar Labor

White collar labor, unlike blue collar, is often not as repetitive as blue collar labor and not nearly as mediated by measurement. There are certain types of white collar jobs that can be very mundane or repetitive, but overall are perceived as involving more creativity and problem solving. As mentioned above, this type of work is not measured or evaluated hourly on any real time based metric. In fact, one of the major benefits of white collar labor is the freedom to accomplish tasks in whatever fashion so long as the tasks are completed by their due date, thus allowing much more creativity within the workspace. Measures of efficiency and monitoring do not apply here like they do in blue collar labor, in fact, the concept of micromanagement is seen as extremely negative and harmful to the freedom and flow of creativity required to accomplish certain tasks. There is generally no required rate of task accomplishment, again, so long as all tasks are complete by their due dates. As was seen during the pandemic with “work from home,” this labor is not physically bound to a certain workplace. Whereas blue collar labor can be done only at a specific workstation, white collar labor can be done almost anywhere depending on the internet requirement of the task. However, I observed something quite peculiar during the pandemic: there are seemingly positions in the white collar industry that can not work from home, they are deemed essential and required to work on site in order to “better serve the business.” This made me wonder, what makes these positions markedly different from other white collar positions and what kinds of issues can arise because of these differences?

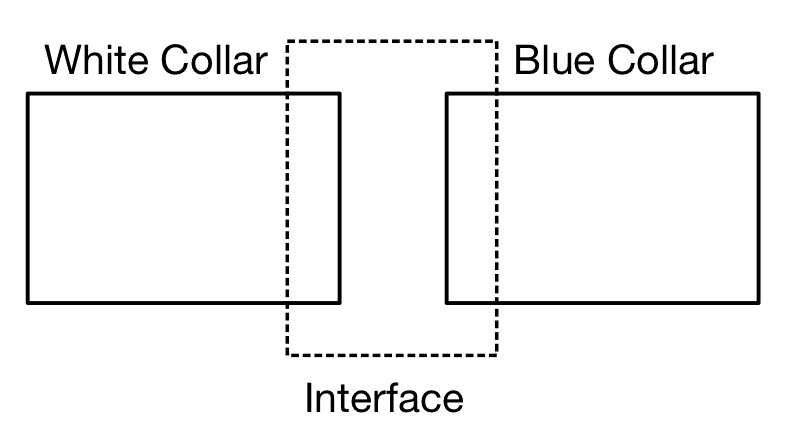

Between Collars: Subsystem Interfaces

It flows logically that when there are two highly interactive subsystems in an organization such as the direct labor and its indirect labor there must be a point (or points) of interface between the systems (see figure 1). Consider the manufacturing engineer who is considered a white collar worker yet must often tend to the needs of the blue collar workspace such as troubleshooting equipment or processes by physically moving from the white collar space (i.e. the office) to the shop floor and then doing work in that space. This worker must navigate both the paces and expectations of white and blue collar labor which poses its own kind of challenges. These workers bring technical expertise through their education (which I will discuss in later sections) to solve pressing problems in the blue collar space in order to mitigate the dreaded “down time” which is a length of time where manufacturing processes cannot be completed due to technical or logistical issues. Their importance to the day-to-day operations binds them physically to the blue collar workspace and restricts certain kinds of white collar freedoms afforded to some of their colleagues. Because of this, this worker must constantly shift between white collar and blue collar modes of productivity and priorities which I believe causes a certain kind of stress for the worker. This stress appears to arise from a different kind of root cause than from what stresses arise in solely white or blue collar labor.

In Summary

The reading material for this week served as a jumping off point to understand what kinds of work are being done in a manufacturing facility and how a different kind of work may arise between the interaction of these systems. As briefly explained, the workers at the interface deal with a different kind of stress as opposed to the other two. In the next few sections I will use more of the texts to discuss the history of both subsystems, how this shaped the expectations of labor, and the contemporary issues currently caused by those expectations. But in order to that I will take the next section to diagram the state and flows of work between and within these subsystems to visualize a typical network of labor in manufacturing organizations.

Leave a comment